FILMINK by Dov Kornits

July 2, 2020

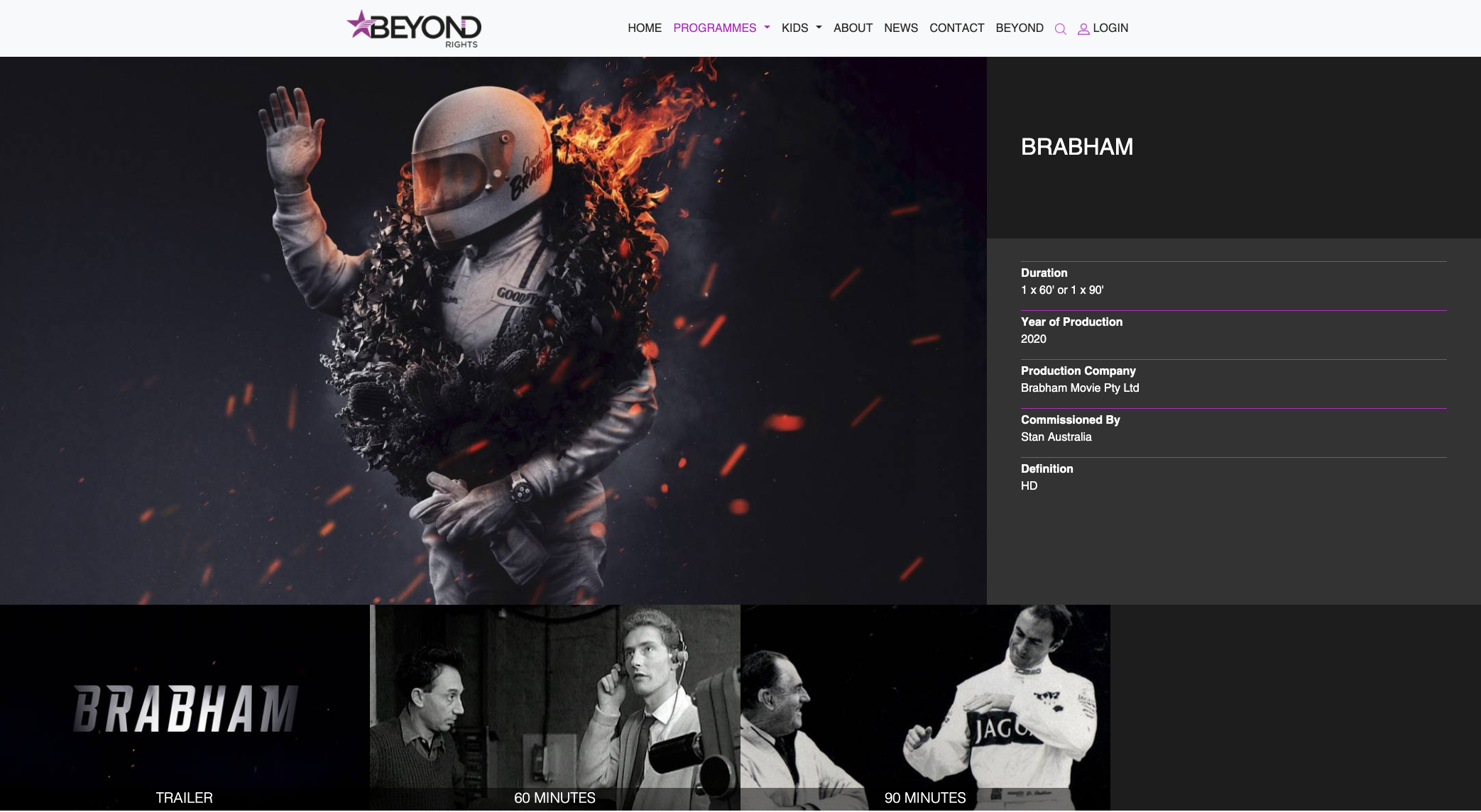

The actor turns producer/director to tell the story of Australian icon Jack Brabham.

“I recall some of my earliest memories were being allowed to stay up late to watch Michael Schumacher dominate the sport through the 1990s. I always had an interest to get closer to the F1, its icons and the enigmatic world in which it exists,” says Ákos Armont, who makes his dreams a reality with the documentary Brabham, his very first but highly accomplished feature as a director.

Sir Jack Brabham is an Australian icon, an Australian race car driver, Formula One World Champion in 1959, 1960 and 1966 and founder of the racing team and race car with his name on it. Brabham’s sons have also entered the race car arena to great success, but the original remained an enigma, even to his children, until his passing on the Gold Coast in 2014 at the age of 88. Born in the south western Sydney suburb of Hurstville, like many Australian icons of the period, Brabham made his name by heading overseas to follow his dreams. His is a fascinating story of a simple, but very complicated man, who forged a fortune and Australia’s reputation as performing well about our weight.

And it’s all here in Ákos Armont’s comprehensive, uncompromising portrait, Brabham.

You’ve done a bunch of acting until now (Spirited, Janet King, House Husbands, The Railway Man). Was filmmaking always something that you were hoping to pursue, along with acting?

I was fortunate to be mentored by producer Michelle Sahayan following our time working together on Jonathan Teplitzky’s The Railway Man. Michelle encouraged me to pursue my interest in writing and adapting biographical material into content for film and tv. My appetite for creative development and collaboration has only increased as I’ve taken a step back from fronting the camera and working behind it.

How did you become involved as director?

In 2013, I began collaborating with a friend on the idea of developing Sir Jack’s story into a feature-length documentary. Sadly, not long after we had our first planning meeting, Sir Jack passed away in May 2014. Sir Jack’s passing was a big blow to our ambitions and ultimately, I ended up pursuing the project independently; first as producer, then as writer/producer and eventually as director as well. We had invited an experienced director onboard early in the development process, however given the intimate and often extended development/production process that documentary involves, it made sense for me to take over the reins and realise the film I had originally set out to make.

Was it difficult to convince the subjects and other people that you should be directing the film?

I spent 3 years investing everything I had into building a vision for the film and establishing grass-roots support for the idea with individuals and motoring organisations like the Australian Racing Drivers’ Club (Sydney Motor Sport Park), the Historic Sport and Racing Car Association of NSW and, of course, the Australian Grand Prix Corporation. I was fortunate to find a champion for the film in my producing partner Antony Waddington (The Eye of the Storm), who subsequently helped build an experienced team around the idea. I never intended to direct Brabham. I am humbled by the experience I’ve had and the trust that David Brabham, the Brabham family and our team of supporters and investors have put in me to guide this film to completion. As is sometimes the case with documentaries, the subject dictates where the film ends up and this couldn’t be more true for our film. Our challenge was to glean an insight into a sporting hero, Sir Jack Brabham, that had been clouded with decades of well-manicured and cultivated mythology; at times the process felt like peeling back layers of an onion only to find that the layers, once gone, left us with nothing more than the experience of having peeled an onion. This search for the man behind the myth became the central focus of the film.

How long was the process of making the film?

From end to end about 7 years; 3.5 years of early development, and 3.5 years of development/production and post-production. Screen Australia’s Gallipoli Clause meant that we were in both development and production in some instances, due to the time-critical nature of many of the interviews we needed to secure.

Did you have Director’s Cut, or was involvement from Brabham family something that you needed to be mindful of?

We retained Director’s Cut, yes. This was particularly important as we discovered midway through filming that David Brabham was in high-level negotiations with Australian interests to relaunch the Brabham marque globally with the development of a new super-car, the BT62. Given the obvious commercial interests around such a substantial investment in the future of the Brabham brand, it was critical that the film stood apart from any interference by third-party interests. I have to say that, for the most part, David Brabham was a true ally to this approach. We had many discussions around the need for editorial independence and the value to presenting Sir Jack ‘warts and all’. My interest was ultimately centred around gaining an insight into Jack Brabham ‘the man’, and over time it became clear that this would only really be possible to achieve by gaining a deeper insight into his sons David and Geoff Brabham. I thank them for their faith and willingness to support the film’s objectivity and independence.

How much archive/original/recreation is the film comprised of, and why?

The film is predominantly a mix of archival and original content, with some recreation and stylised animation to help bridge the sequences where there was an abject lack of content for us to draw on. I know many viewers will relish seeing legends of motorsport Sir Stirling Moss, Sir Jackie Stewart, John Surtees talking directly to camera; their anecdotes are wily, filled with wit and nostalgia. We’re also lucky to have the BAFTA Award winning Grayson Perry and sequences of Paul Newman (digitally restored from the Academy Archives) commenting on the psychology and philosophy of motorsport and masculinity; which will resonate with some audiences I’m sure. The archive footage we use, largely tells the story of Sir Jack’s racing career, with glimpses of his personal life and the animation reflects the more apocryphal anecdotes with a wry sense of humour which I hope audiences will appreciate.

Stylistically, the documentary makes interesting choices – was that something you figured out along the way, or were there touchstones for you as a filmmaker that you were emulating/inspired by?

I’m very interested in the intersection between memory and mythology; in the case of our film, particularly as it relates to sporting heroes and specifically to that of Jack Brabham.

In the few short decades between Sir Jack’s departure from Formula 1, a singular monomyth about his achievements and, perhaps more superficially, about his character, has prevailed publicly. But this myth gives little insight into his ‘key drivers’ and the impact he left on those closest to him. Moreover, the mythologising of ‘masculine accomplishments’ can have a very direct impact on subsequent generations of not only aspiring ‘sportsmen’, but the very idea of manliness itself.

The closer I felt we got to understanding Jack Brabham ‘the man’, the further he seemed to recede into the myth surrounding him. Like Peter Pan’s shadow, Jack was not interested in being pinned down and so this became a guiding stylistic theme for us i.e. hyperbole, contradiction and subversion are all tools used in the film to suggest the challenge of identifying a singular ‘truth’ to who JB was. Jack remains a mystery and this idea of mystery would also inform the stylistic approach to the filmmaking.

As a mythological hero, Jack would, in turns, become everything and nothing to the film we were actually making; a resident ghost unwilling to give up his secrets so easily. Eventually, the decision was made to turn to Jack’s sons, David and Geoff for a deeper insight into their father. David has laboured under his father’s shadow for much of his life, through aspiration and comparison, he has had to endure the frustrations and challenges of being ‘the son to the legend’. The old adage that the sins of the father become those of the son also plays out in the film, as David grapples to not only reinvent himself in mid-life, but to step out from under the looming shadow of his hero dad; a shadow which grows ever longer with each passing year through the media’s manipulation of Sir Jack’s legacy.

The film uses visual metaphor and the intercutting of archival content from across different decades, as well as a vocal soundtrack, to highlight how memory and mythology can coalesce to provide a commonly accepted idea of an icon, like Sir Jack. An idea, which when interrogated, can disintegrate as quickly as it was conceived.

Finally, on an emotional level, the film addresses the theme of fathers and sons; and the complex and often fraught relationship between them. The film structure reflects the handover of family legacies from one generation to the next and, I hope, may act as a call to action for viewers to interrogate their own relationships with their parents and preconceptions about themselves and what they are capable of achieving in their own lives.

What’s next?

Aurora Films [production company founded by Ákos] has recently announced its acquisition of Behrouz Boochani’s award winning book No Friend But The Mountains: Writing From Manus Prison, to be adapted into a feature film in collaboration with Hoodlum (Qld.) and Sweet Shop & Green (Vic.). Our team is also working closely with a director on adapting the much lauded Helen Garner novel The Spare Room into a feature film. While I remain invested and open to pursuing more motorsport and sporting related content, I’m delighted to be expanding our slate to incorporate a wide range of stories and issues that our team cares deeply about.